Post Medieval Stoneware Industry of the Rhineland : A Shining Example of Frankish Pottery

In this issue, Pot Spot stays in Germany and moves on 700 years to the Post-Medieval stoneware industry of the Rhineland. Vast quantities of products from these factories were imported into Britain in Tudor and Stuart times reflecting the convivial atmosphere which prevails in the 16th and 17th centuries, as the majority of the vessels were either for drinking from or pouring out of.

Since Roman times, alcohol has been one of the more important commodities traded from the continent and until the widespread use of glass, containers were commonly made of pottery. However, ceramic cups and mugs for drinking did not become universally popular until the end of the 15th century. During the medieval period, the average tippler would have downed his daily pint food vessels of silver, pewter, glass, leather or horn, but most frequently he would have imbibed from ‘ashin cuppis’ i.e. wood. Needless to say, the latter chipped, split and broke in the same way as pottery, but also became rather unsavoury after repeated use. Consequently the idea of smooth glazed mugs, easy to clean and agreeable to drink from caught on and large numbers found their way to Britain in German cargoes: entries in the Southampton port books, for example, record extensive importation in the late 1400s.

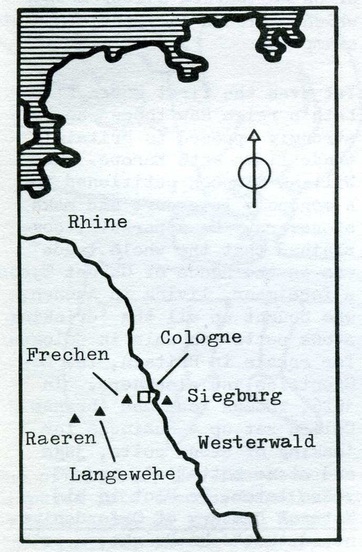

The tradition of high-fired pottery was a long established one in Germany, fine quality wheel-thrown wares fired to near stoneware temperatures were being produced in the Rhineland area in the 10th century AD. This area had always been a spot favoured by potters and the major stoneware manufacturers were centred largely around Cologne.

Since Roman times, alcohol has been one of the more important commodities traded from the continent and until the widespread use of glass, containers were commonly made of pottery. However, ceramic cups and mugs for drinking did not become universally popular until the end of the 15th century. During the medieval period, the average tippler would have downed his daily pint food vessels of silver, pewter, glass, leather or horn, but most frequently he would have imbibed from ‘ashin cuppis’ i.e. wood. Needless to say, the latter chipped, split and broke in the same way as pottery, but also became rather unsavoury after repeated use. Consequently the idea of smooth glazed mugs, easy to clean and agreeable to drink from caught on and large numbers found their way to Britain in German cargoes: entries in the Southampton port books, for example, record extensive importation in the late 1400s.

The tradition of high-fired pottery was a long established one in Germany, fine quality wheel-thrown wares fired to near stoneware temperatures were being produced in the Rhineland area in the 10th century AD. This area had always been a spot favoured by potters and the major stoneware manufacturers were centred largely around Cologne.

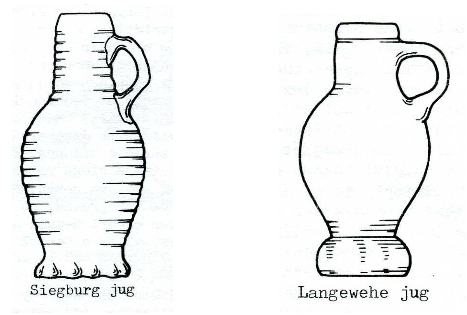

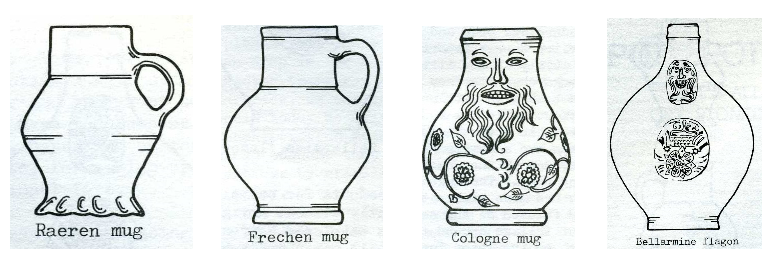

The term ‘stoneware’ is used to describe pottery which has been fired to a very high temperature, usually over 1250° centigrade, causing the clay to vitrify. The clay used for this process is specially chosen to withstand heat without distorting the distinctive 'orange-peel' 'glaze effect is achieved by throwing salt into the kiln when the necessary heat has built up. The salt gives off a sodium vapour which combines with the free silica in the body of the pot to form a glaze, the colour depending on the iron oxides present in the clay. Most often the surfaces turn out a grey or brown, sometimes with a ‘bronzy’ result. As one of the main advantages of stoneware is its low porosity, the application of glaze is for the most part decorative, Siegburg products for example, are frequently without any glaze whereas developed Raeren and Westerwald wares are enhanced with underglaze blue and purple. The earlier Raeren imports consisted mainly of the little globular mugs characterised by a frilled base with little other decoration, while the equivalent products from the Frechen workshops had a simple flat foot and a cordon at the junction of neck and body. The mugs from Cologne are more elaborate with moulded friezes on the neck and bands of foliage around the middle; on the later forms, face masks appear at the neck and monogram bands on the body of the pot. The face masks continue into the 17th century, especially on flagons which have come to be known as 'Bellarmines'. It has been said that the caricature was meant to represent Cardinal Bellarmine, one of the greatest theologians of his time who wrote three influential treatises on heresy. However the Duke of Alva has also been suggested as a likely candidate. Nevertheless, quasi religious mottoes such as ‘Trink und esst, Got nicht vergesst’ were often printed around mugs and also quite conveniently, dates sometimes appear in coats of arms or on hallmarked silver mounts which enriched the more elaborate examples.

Yet even the first Queen Elizabeth's reign saw those who were strongly opposed to Britain's trade links with Europe. One William Simpson petitioned for a monopoly to export and make stoneware. He apparently complained that the whole trade was in the hands of Garnet Tynes, a foreigner, living in Aachen, who bought up all the ‘drinking stone potts’ on sale in Cologne for resale in Britain, the Low Countries and elsewhere. In 1626, Thomas Rous and Abraham Cullen set up a business for ‘making of stone potts, jugs and stone bottells’, and 50 years later, Dr Plot in his Natural History of Oxfordshire noted that John Dwight, a potter from Fulham, had discovered the secret of Cologne stoneware, and that the Glass Sellers Company of London had a contract to buy his work rather than imports. By the end of the 17th century the German trade was in decline as more and more English factories were established to create goods which could match the superior standards of their continental counterparts.

Jane Holdsworth