In Roman times public buildings often had very elaborate decorations often including marble wall veneers and wall mosaics. Private individuals could rarely afford such luxuries and usually decorated their houses with painted piaster according to their means and taste.

The walls and ceilings of timber framed and stone buildings were normally plastered and, if the owner wished, decorated with paint. Perhaps plain coloured walls and walls with stripes were commonest of all. The last is found in humble circumstances. The stripes are often in a wide range of colours, often clashing, on a white background. Slightly more sophisticated was the stippled effect produced by splashing paint from a brush. This decor could be done with little effort and expense and was therefore normally used in shops, barrack blocks and unpretentious dwellings.

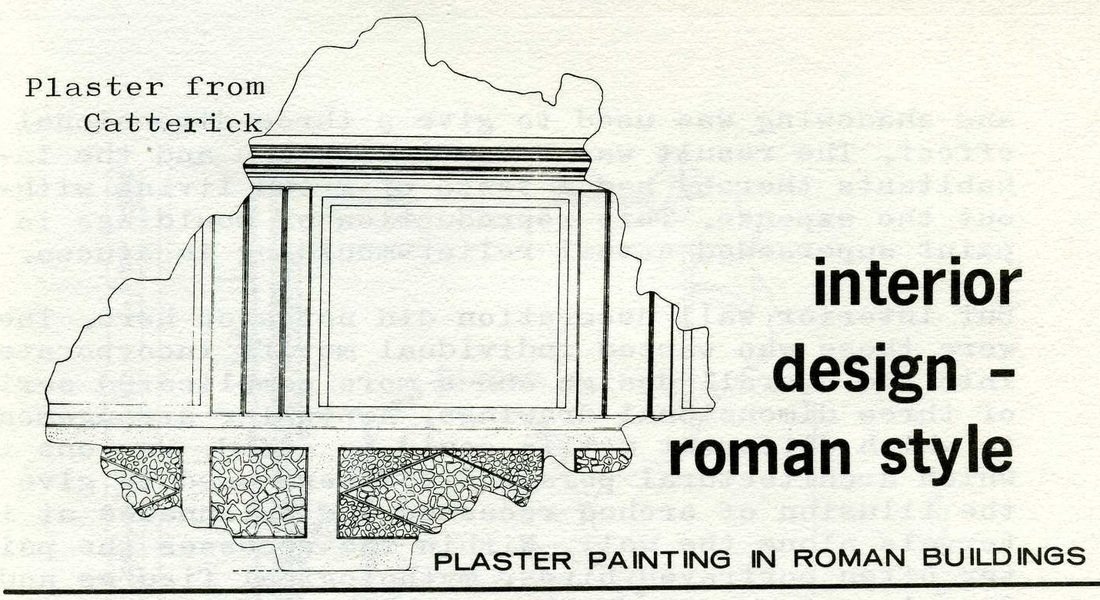

For those who desired more elaborate surroundings the walls could be painted to give the effect of paneling. This was done quite simply. The wall was divided into three parts with the lowest two to three feet painted to imitate dado paneling. About four to five feet above the dado was then decorated to resemble recessed paneling with a cornice moulding; across the top. A frieze sometimes surmounted the cornice; otherwise it was left plain. The dado paneling was often painted to resemble marble veneer and shadowing was used to give a three-dimensional effect. The result was a convincing one and the inhabitants thereby had a taste of grand living without the expense. This reproduction of mouldings in paint superseded actual relief-moulding in stucco.

The walls and ceilings of timber framed and stone buildings were normally plastered and, if the owner wished, decorated with paint. Perhaps plain coloured walls and walls with stripes were commonest of all. The last is found in humble circumstances. The stripes are often in a wide range of colours, often clashing, on a white background. Slightly more sophisticated was the stippled effect produced by splashing paint from a brush. This decor could be done with little effort and expense and was therefore normally used in shops, barrack blocks and unpretentious dwellings.

For those who desired more elaborate surroundings the walls could be painted to give the effect of paneling. This was done quite simply. The wall was divided into three parts with the lowest two to three feet painted to imitate dado paneling. About four to five feet above the dado was then decorated to resemble recessed paneling with a cornice moulding; across the top. A frieze sometimes surmounted the cornice; otherwise it was left plain. The dado paneling was often painted to resemble marble veneer and shadowing was used to give a three-dimensional effect. The result was a convincing one and the inhabitants thereby had a taste of grand living without the expense. This reproduction of mouldings in paint superseded actual relief-moulding in stucco.

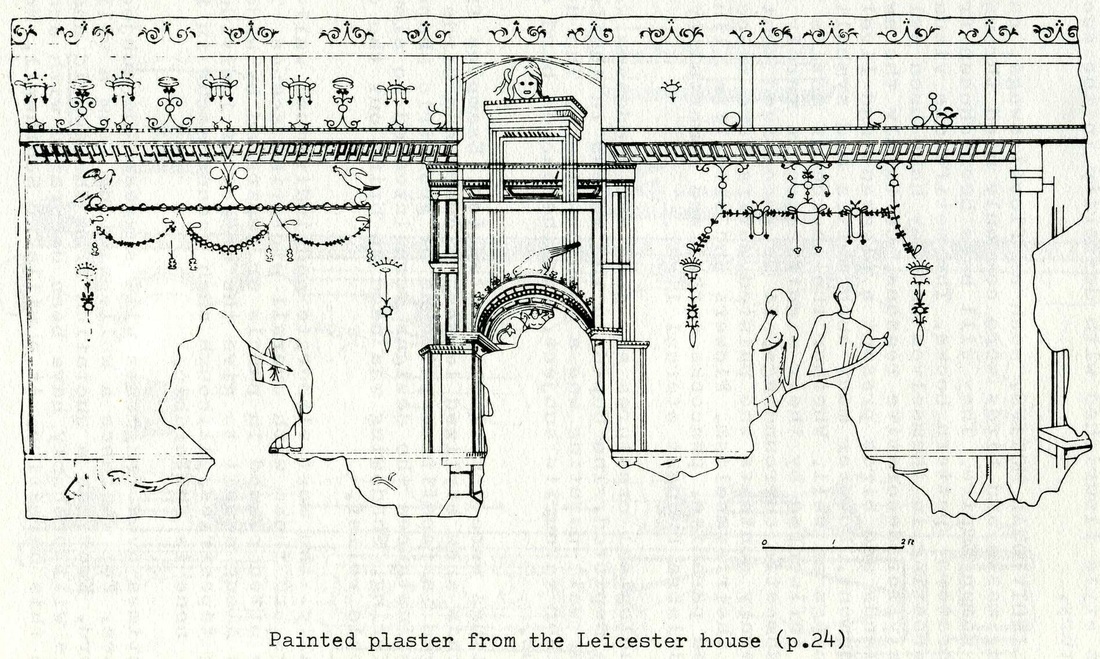

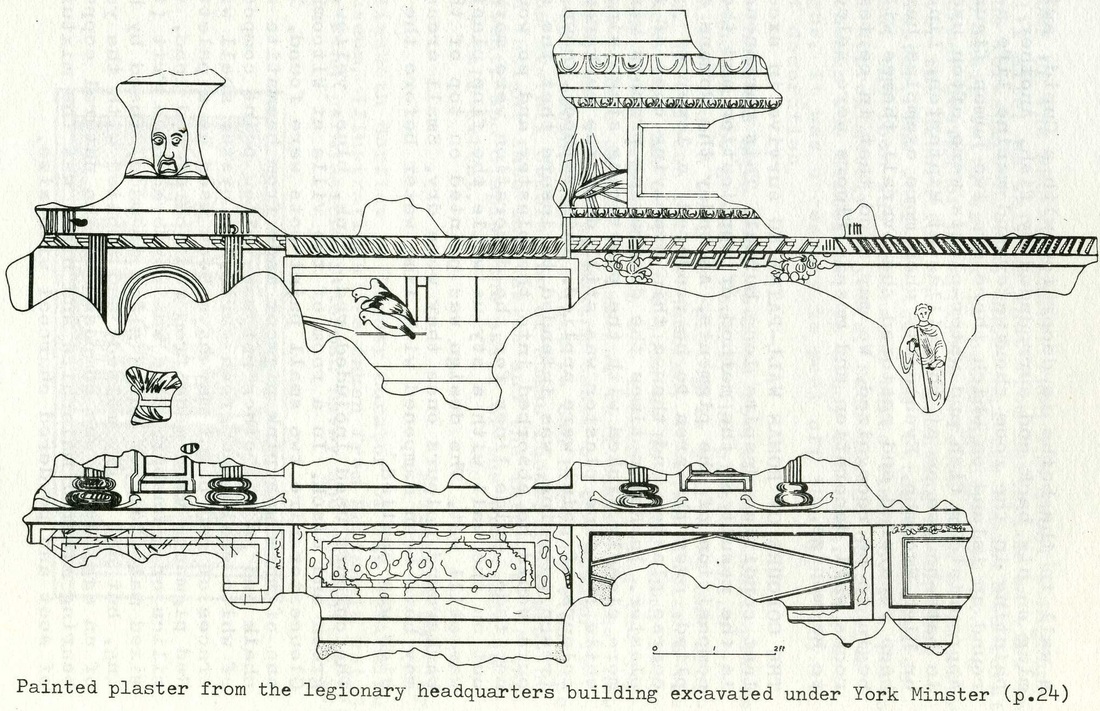

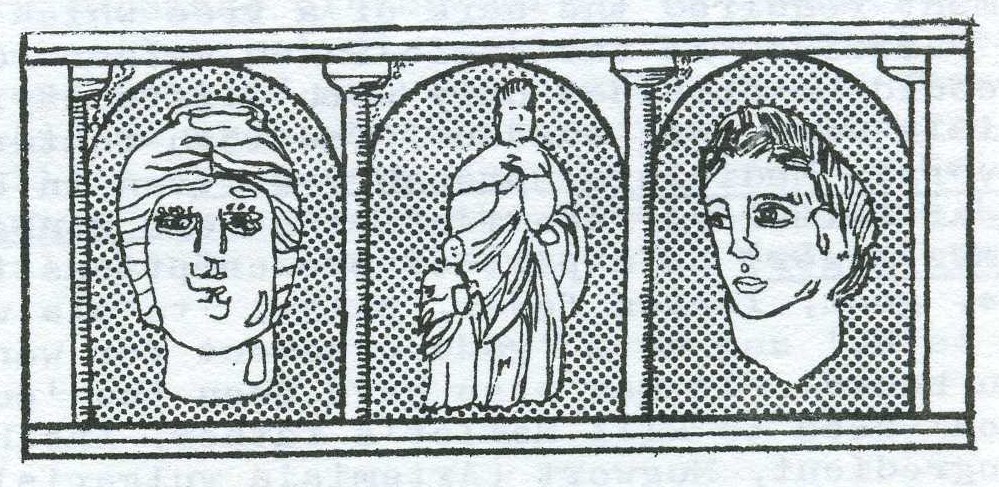

But interior wall decoration did not stop here. There were those who wanted individual motifs incorporated into the overall design and a more complicated series of three dimensional drawings. A popular arrangement, to which different motifs could be added, was one in which architectural perspectives were used to give the illusion of arched recesses and colonnades at intervals along the wall. Within the recesses the painter often portrayed birds, mythological figures and floral sprays and, in the area between the architectural perspectives, draped human figures were often painted facing into the room.

A fine example of this style, which was common in Italy itself, was found in a second-century Roman courtyard house in Leicester (see illustration). Fragments of decorated piaster from Bishophill, York found by the York Archaeological Trust in 1973, are in the same style. Among the fragments are the chest and shoulders of a human figure and the top of an arched recess. A more complete example from York is the reconstructed plaster from the legionary headquarters building, now on exhibition in the undercroft of the Minster (see illustration). The wall-plaster stands about ten feet high and has niched recesses at intervals and a draped human figure in the area between the niches. There is a tragic mask painted in the frieze, as in the Leicester wall-painting. However, the York example is approximately two hundred years later in date than the Leicester painting and indicates that the style and motifs long continued to be used through the Roman period.

A fine example of this style, which was common in Italy itself, was found in a second-century Roman courtyard house in Leicester (see illustration). Fragments of decorated piaster from Bishophill, York found by the York Archaeological Trust in 1973, are in the same style. Among the fragments are the chest and shoulders of a human figure and the top of an arched recess. A more complete example from York is the reconstructed plaster from the legionary headquarters building, now on exhibition in the undercroft of the Minster (see illustration). The wall-plaster stands about ten feet high and has niched recesses at intervals and a draped human figure in the area between the niches. There is a tragic mask painted in the frieze, as in the Leicester wall-painting. However, the York example is approximately two hundred years later in date than the Leicester painting and indicates that the style and motifs long continued to be used through the Roman period.

The second-century work is more delicately conceived but one may ask whether this just reflects the technique of more skilled craftsmen, not a deliberate choice in technique. When more examples of wall-painting have been excavated in dated contexts, we may begin to see the answer to this question. From what evidence there is at the moment it seems that this style flourished with dexterity in the second century.

The individual motifs, such as floral swaps, candelabra, masks and birds were commonly used throughout the Roman Empire. They will have been chosen from decorators’ pattern books. The motifs are visually interesting in themselves and may have been selected purely for decorative reasons. Certainly the swaps of garlands and birds present a pleasant and silvery environment. However many such motifs had symbolic meanings as well. Whether the choice of motifs was at all influenced by their significance is rarely clear in domestic surroundings. It is recognised that in funerary contexts the painted motifs were selected for their symbolism. Flowers and wildlife illustrated paradise, peacocks symbolised immortality and candelabra brought eternal light.

Mythological creatures and gods and goddesses were also depicted. The Cupid in the recess in the Leicester wall-painting was a popular figure. The dove, another favourite subject, was the sacred bird of Venus.

Ceilings were sometimes painted too. Examples from Britain show stylised leaves, flowers and birds arranged in repetitive patterns of geometric shapes. In some instances the designs were intended to simulate coffering. Shadowing was used to bring out the design in bold relief.

Finally, the most elaborate and individual wall-paintings are those with overall pictorial scenes. These were often placed in panels or separated by wide borders along a wall to give the effect of individual hung tapestries. Although such scenes occur in Britain, none is restorable.

Sometimes even fragments will suggest the subject of scenes. For instance a wall-painting from a villa at Oxford, Kent has a quotation from the Aeneid and the walls will probably have been decorated with scenes from this narrative. At a villa at Southwell, Notts., a wall in the baths is decorated with a Cupid, swimming on his back and surrounded by fish. Another painting in the room shows water and marine life around an island on which there are two human figures. Appropriately fish and water-plants were often used in bathhouses as at the villas at Winterton, Lincs. or High Wycombe. Eventually when more examples have been recovered and restored the overall themes will begin to be recognised. We may find that in certain rooms will decoration and mosaic floors were selected to harmonise.

The colours of Roman wall-painting survive in excellent condition despite long burial. This permanency is the result of the method of application and the composition of the pigments. As today the Romans applied, over the area to be rendered, a layer of coarse plaster and then a thin overlying coat of fine plaster. In Roman times the decorating process was more closely linked with the plastering stage since while the fine plaster has still damp the background colours of paint were applied. This method, known as fresco painting, was intended to insure that the colour would be absorbed into the piaster and so would not fade. Guide lines for the decoration were marked out on the wall with a stylus while the fine plaster was still wet. The design was painted on top of the background colours once they were dry. Small areas may have been dampened with lime water before the design was applied.

The individual motifs, such as floral swaps, candelabra, masks and birds were commonly used throughout the Roman Empire. They will have been chosen from decorators’ pattern books. The motifs are visually interesting in themselves and may have been selected purely for decorative reasons. Certainly the swaps of garlands and birds present a pleasant and silvery environment. However many such motifs had symbolic meanings as well. Whether the choice of motifs was at all influenced by their significance is rarely clear in domestic surroundings. It is recognised that in funerary contexts the painted motifs were selected for their symbolism. Flowers and wildlife illustrated paradise, peacocks symbolised immortality and candelabra brought eternal light.

Mythological creatures and gods and goddesses were also depicted. The Cupid in the recess in the Leicester wall-painting was a popular figure. The dove, another favourite subject, was the sacred bird of Venus.

Ceilings were sometimes painted too. Examples from Britain show stylised leaves, flowers and birds arranged in repetitive patterns of geometric shapes. In some instances the designs were intended to simulate coffering. Shadowing was used to bring out the design in bold relief.

Finally, the most elaborate and individual wall-paintings are those with overall pictorial scenes. These were often placed in panels or separated by wide borders along a wall to give the effect of individual hung tapestries. Although such scenes occur in Britain, none is restorable.

Sometimes even fragments will suggest the subject of scenes. For instance a wall-painting from a villa at Oxford, Kent has a quotation from the Aeneid and the walls will probably have been decorated with scenes from this narrative. At a villa at Southwell, Notts., a wall in the baths is decorated with a Cupid, swimming on his back and surrounded by fish. Another painting in the room shows water and marine life around an island on which there are two human figures. Appropriately fish and water-plants were often used in bathhouses as at the villas at Winterton, Lincs. or High Wycombe. Eventually when more examples have been recovered and restored the overall themes will begin to be recognised. We may find that in certain rooms will decoration and mosaic floors were selected to harmonise.

The colours of Roman wall-painting survive in excellent condition despite long burial. This permanency is the result of the method of application and the composition of the pigments. As today the Romans applied, over the area to be rendered, a layer of coarse plaster and then a thin overlying coat of fine plaster. In Roman times the decorating process was more closely linked with the plastering stage since while the fine plaster has still damp the background colours of paint were applied. This method, known as fresco painting, was intended to insure that the colour would be absorbed into the piaster and so would not fade. Guide lines for the decoration were marked out on the wall with a stylus while the fine plaster was still wet. The design was painted on top of the background colours once they were dry. Small areas may have been dampened with lime water before the design was applied.

The colours used included red, pink, blue, yellow, green and black. In a room of the villa at Witcombe, Gloucestershire two small paint pots were found. In one of them was pink pigment made from haematite and chalk and in the other pot was yellow paint composed of white chain and green earth. An oyster shell with traces of red paint may have been used as a palette. Red pigments here made from red ochre, red lead, vermilion or cinnabar. Blue was pondered blue frit (the mixed materials of which glass is made, fused by heating, but not fully melted) and applied with the yolk of an egg. Green was composed on the natural copper-bearing mineral malachite and black was the mixture of soot and powdered charcoal with size.

Some of the recent plaster from the Trust’s Bishophill site, as well is that from Catterick on view in the Yorkshire Museum, shows how the Romans redecorated their walls either by painting directly over a former design or by applying a breed skin of plaster over the decoration and then painting on the new plaster. The wall-plaster from Catterick indicates that the room was decorated three times over a period of approximately 60 years. Each of the decorative schemes was different. To study the underlying designs, it was necessary to peel off the upper layers of decoration.

Techniques have been devised for lifting wall-plaster found in the ground. Usually the plaster which has fallen from a wall or ceiling is shattered and broken. The pieces can be jumbled, in which instance the excavator can only lift them as he finds them, decorating their positions in the trench. Solving the jigsaw-puzzle can be an immense task taking months. However, the reward of making sense of the design is great indeed. Here at last we can begin to visualise the overall decoration of Roman rooms. They provide an insight into the tastes and the interests of the client, and display the skill of the craftsman to its full extent.

Elizabeth Hartley

Elizabeth Hartley is Deputy Curator of The Yorkshire Museum. Illustrations are taken from Britannia vol 3 by kind permission of Norman Davey and the editor.

Some of the recent plaster from the Trust’s Bishophill site, as well is that from Catterick on view in the Yorkshire Museum, shows how the Romans redecorated their walls either by painting directly over a former design or by applying a breed skin of plaster over the decoration and then painting on the new plaster. The wall-plaster from Catterick indicates that the room was decorated three times over a period of approximately 60 years. Each of the decorative schemes was different. To study the underlying designs, it was necessary to peel off the upper layers of decoration.

Techniques have been devised for lifting wall-plaster found in the ground. Usually the plaster which has fallen from a wall or ceiling is shattered and broken. The pieces can be jumbled, in which instance the excavator can only lift them as he finds them, decorating their positions in the trench. Solving the jigsaw-puzzle can be an immense task taking months. However, the reward of making sense of the design is great indeed. Here at last we can begin to visualise the overall decoration of Roman rooms. They provide an insight into the tastes and the interests of the client, and display the skill of the craftsman to its full extent.

Elizabeth Hartley

Elizabeth Hartley is Deputy Curator of The Yorkshire Museum. Illustrations are taken from Britannia vol 3 by kind permission of Norman Davey and the editor.