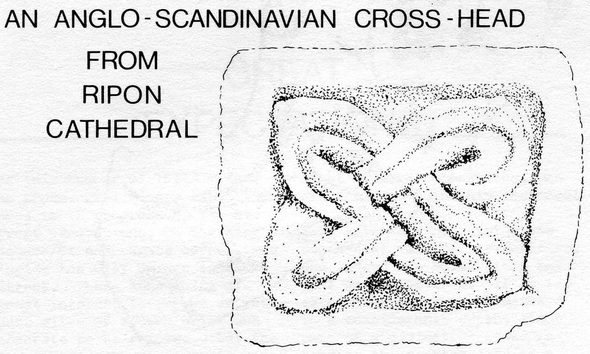

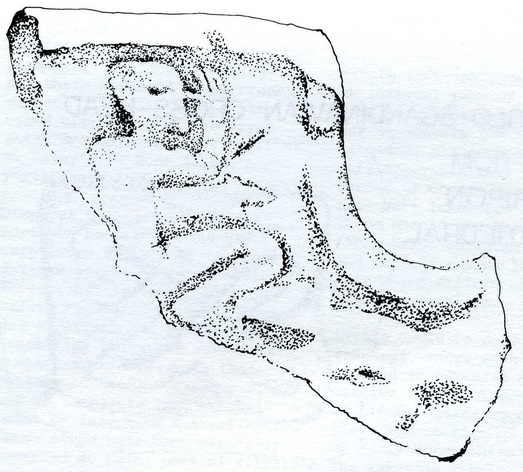

The sculptural fragment, whose circumstances of discovery are referred to in the previous article (‘Keyhole Archaeology: Ripon Cathedral Crypt’), consists of the upper arm and one lateral arm of a free-armed sandstone cross. One face and the surviving end field contain interlace patterns, but the principal face is filled with illustrative carving in low relief.

Within the upper arm a seated figure is depicted in profile, his right hand raised to his mouth. Below his feet and extending into the lateral arm is the head of a beast with a domed brow, splayed jowl and incised elliptical eye. This scene is identified as Sigurd sucking has thumb over the dead dragon Fafnir, a popular theme in the illustrative sculpture of northern England in the tenth century.

The scene comes from a complex story of greed and revenge, in which Fafnir, his brother Regin, and has father acquire a huge ransom of gold from the gods in recompense for the killing of another brother. The two surviving sons kill their father for his share, then Fafnir, in a bid for outright possession, turns himself into a dragon and lies upon the gold. Regin, showing admirable initiative, urges on the hero Sigur to slay Fafnir. Sigur obliges, and is then asked by Regin to roast the dragon’s heart. In the process he burns his thumb, sucks it better (the scene on the cross-head) and in doing so tastes the dragon's blood, which imbues him with supernatural knowledge and allows him to hear the birds singing that Regin will double-cross him. Sigurd then kills Regin, but is subsequently beset by further tribulations, which need not concern us here.

The decorative scheme and the interlace of this cross-head were matched by another Ripon piece, once in the crypt but now no longer in the cathedral. Drawings of it show a cross-head of similar shape and size, with interlace ornament on the reverse face and arm tips, and illustrative sculpture on the principal face, consisting of two confronting birds on either side of a domed boss. It seems likely that the two cross-heads were by the same hand, since they are decoratively and technically analogous. Both belong to the tenth century, and the Sigurd reference on the new piece testifies to its Anglo-Scandinavian period context.

J.T. Lang

(J. T. Lang is a lecturer in the Department of English at Neville’s Cross College, Durham. He as at present engaged in compiling Yorkshire volume of the British Academy’s Corpus of Pre-Conquest Sculpture.)

J.T. Lang

(J. T. Lang is a lecturer in the Department of English at Neville’s Cross College, Durham. He as at present engaged in compiling Yorkshire volume of the British Academy’s Corpus of Pre-Conquest Sculpture.)