Colourful Floors

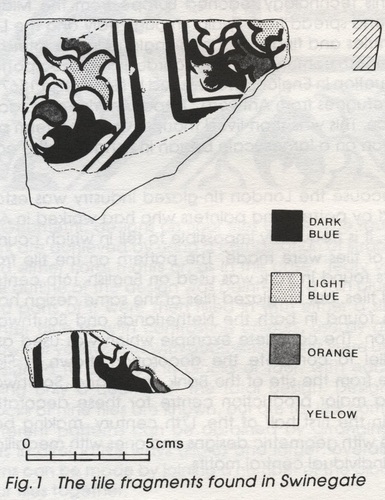

Pieces of two tin-glazed paving tiles were among the gems found on the Trust's latest excavation in the Swinegate area. These colourful and attractive tiles are nearly 2cm thick, and fairly small, 10.3cm square. The edges have been slightly undercut so the tiles could be fitted close together, rather than with a gap as is the practice with most modern tiles. The decoration of these tiles is achieved by the use of coloured glazes, and is technically known as tin-glazed polychrome. In this case the decoration comprises four colours, light and dark blue, orange and yellow, on a white background (Fig.l).

Manufacturing these tiles was a complex and elaborate business. The tiles had to be fired twice, first to a 'biscuit' stage and again once the glaze and decoration had been added. The addition of tin to lead glazes makes them white and, more importantly, opaque, thus providing a clean light-coloured background for what are often complex and elaborate designs. Mineral ox-Ides were added to the basic glaze to colour it, cobalt for blue, copper for green, antimony for yellow and manganese for a range of colours from pale amethyst to dark purple. These colours could then be painted with great precision on the smooth, dry background glaze and were absorbed into the glaze during firing.

This technology reached Europe from the Middle East and spread from Spain, through Italy and the Low Countries and finally reached England in the later half of the 16th century. The first recorded tin-glazed pottery production In England was started In Norwich In 1567 by two refugees from Antwerp, Jaspar Andries and Jacob Janson. This was short lived though, and long-term production on a larger scale began in London in the early 1570s.

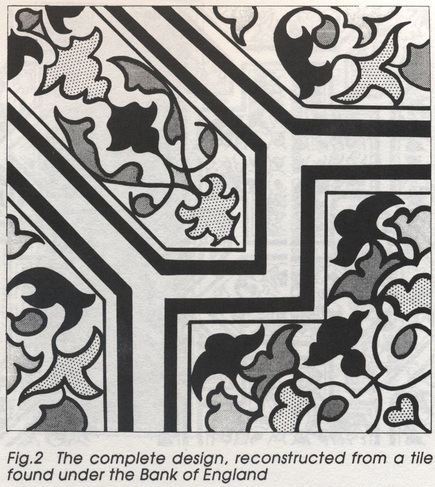

Because the London tin-glazed Industry was established by potters and painters who had worked in Antwerp, it is frequently impossible to tell in which country pots or tiles were made. The pattern on the tile fragments found in York was used on English 16th century inlaid tiles, but tin-glazed tiles of the same design have been found in both the Netherlands and Southwark, London. The complete example which was used as a parallel to complete the decoration shown in Fig.2 came from the site of the Bank of England. Southwark was a major production centre for these decorative tiles in the first half of the 17th century, making both those with geometric designs and ones with medallions and Individual central motifs.

Manufacturing these tiles was a complex and elaborate business. The tiles had to be fired twice, first to a 'biscuit' stage and again once the glaze and decoration had been added. The addition of tin to lead glazes makes them white and, more importantly, opaque, thus providing a clean light-coloured background for what are often complex and elaborate designs. Mineral ox-Ides were added to the basic glaze to colour it, cobalt for blue, copper for green, antimony for yellow and manganese for a range of colours from pale amethyst to dark purple. These colours could then be painted with great precision on the smooth, dry background glaze and were absorbed into the glaze during firing.

This technology reached Europe from the Middle East and spread from Spain, through Italy and the Low Countries and finally reached England in the later half of the 16th century. The first recorded tin-glazed pottery production In England was started In Norwich In 1567 by two refugees from Antwerp, Jaspar Andries and Jacob Janson. This was short lived though, and long-term production on a larger scale began in London in the early 1570s.

Because the London tin-glazed Industry was established by potters and painters who had worked in Antwerp, it is frequently impossible to tell in which country pots or tiles were made. The pattern on the tile fragments found in York was used on English 16th century inlaid tiles, but tin-glazed tiles of the same design have been found in both the Netherlands and Southwark, London. The complete example which was used as a parallel to complete the decoration shown in Fig.2 came from the site of the Bank of England. Southwark was a major production centre for these decorative tiles in the first half of the 17th century, making both those with geometric designs and ones with medallions and Individual central motifs.

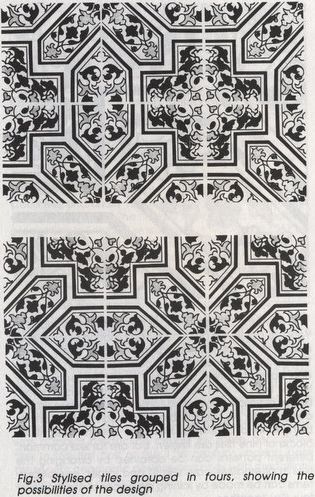

Geometric designs on floor tiles of the type found in York are achieved by using a combination of strapwork and either floral motifs or, as in this case, 'leafy vines'. The outline of the design was painted in a thin blue line and parts of it were then filled in with either a slightly lighter blue or with contrasting colours, usually green, brown or yellow. Tiles with geometric motifs were usually designed to be used in blocks of four, with each tile being only a quarter of the total design. Designs for blocks of nine tiles are known, but are far less common. Different patterns can be obtained by arranging the tiles in alternative ways (Fig.3) and larger, overall patterns can be made by Joining a number of the blocks of four tiles together.

Although these colourful tiles are of a fairly well known type, they are not that common; certainly these are the only pieces I have seen in three years looking at York pottery, whereas fragments of the later and better known blue and white wall files are found quite frequently. Wherever these tiles were originally laid, they must have produced an impressive and colourful floor.

Sarah Jennings