Back to the Chapel

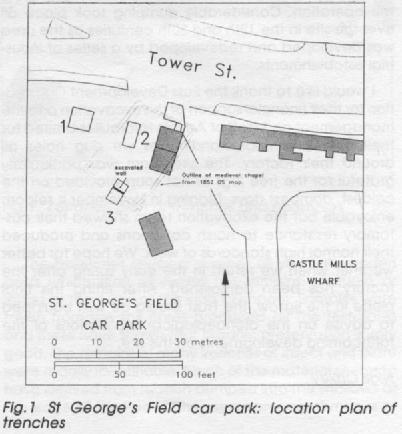

As readers of INTERIM 15/3 will be aware, the proposed construction of a pumping station at the north end of St George's Field car park prompted the York Archaeological Trust to undertake evaluative excavations on the site during October 1990 (Fig, 1; Trenches 1 and 2). The principal cause for concern was that the development would destroy the southern part of St George's Chapel; this chapel, established by the 12th century, but possibly on an even earlier foundation, was the original chapel of York Castle before it came into the hands of the Guild of St Christopher and St George in 1447. Despite the Dissolution, this large masonry building remained largely intact, and it was soon incorporated in a half-timbered building that was used as a workhouse and, finally, a public house, prior to its demolition as recently as 1856.

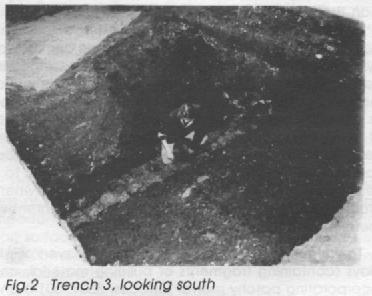

The first phase of excavations showed that archaeological deposits on the site survived, relatively intact, beneath the modern car park. However, they did not reveal to what extent the chapel building itself survived, and so a second phase of evaluative excavation was undertaken in the last week of November 1990, to answer this question. Trench 3 was excavated by machine over the line of the chapel's south wall, as indicated on the 1852 Ordnance Survey map of York. It was evident during the machining that there was a linear, rubble-filled feature where the wall was thought to be, and hand-digging soon exposed a masonry wall (Fig.2).

The first phase of excavations showed that archaeological deposits on the site survived, relatively intact, beneath the modern car park. However, they did not reveal to what extent the chapel building itself survived, and so a second phase of evaluative excavation was undertaken in the last week of November 1990, to answer this question. Trench 3 was excavated by machine over the line of the chapel's south wall, as indicated on the 1852 Ordnance Survey map of York. It was evident during the machining that there was a linear, rubble-filled feature where the wall was thought to be, and hand-digging soon exposed a masonry wall (Fig.2).

The wall was almost a metre north of the position indicated on the 1852 map. This discrepancy could be entirely explained by the difficulty in relating the map to the existing landscape. Another possibility is that the 1852 map is inaccurate; the line of the excavated wall diverges from that on the map, to the west. This suggests that the kink evident in the south wall of the chapel on the 1852 plan was an exaggeration; straightening of the wall would bring it closer to, and on the same alignment as, the excavated wall.

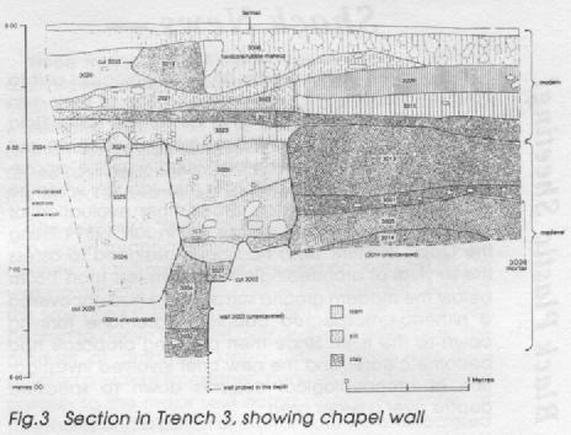

In any case, there can be little doubt that this is the south wall of St George's Chapel. It is 0.7m wide, and it survives to a height of at least 1.3m. The north side of the wall consisted of a course of limestone fragments, aver-aging 0.2m in each dimension and squared only on the visible face. The upper-most course on the south side comprised large limestone blocks, squared on every face and up to him long. Limited excavation against this side of the wall revealed two more courses of lime-stone blocks which, at 0.35m thick, were even larger than those of the upper-most course (Fig.3, 3003); this indicates that the south face was the external face. The wall was mortared, with a limestone rubble core. It was evident that the rubble above the wall represented its partial robbing, presumably during the clearance of the site in 1856. The south side of the wall was robbed to a greater depth, probably due to selective removal of the larger, external-facing stones. The robbing exceeded 1m in depth; nevertheless, as the wall foundation was not reached, it is likely that the wall stood to a height of over 2m in total, and even higher elsewhere around the building if the robbing was less Intensive there.

To the north of the wall were alternating layers of silty clays (containing fragments of building material, and incorporating patchy mortar surfaces; 3001, 3014) and thick clay deposits (3005, 3013), which are thought to be episodes of occupation and raising of the floor level respectively, within the chapel. To the south of the wall, and therefore outside the chapel, there was evidence of dumps (3004, 3032) and pit-digging (3035).

The next identified activity was the robbing of the chapel wall (3002). Unlike Trench 2, there was no evidence of the post-medieval occupation of the chapel, perhaps because the 1856 demolition involved the clearance of such remains. The top 1m of deposits in the trench were mainly the product of the construction of the present car park.

The second phase of excavation reinforced the findings of the first. Hopefully, the evidence that such an important, substantial building lies beneath the car park surface will result in a modification of the proposed development, so that St George's Chapel suffers no further depredation.

Thanks are due to York City Council, which funded the project and provided every assistance. Finally, the excavation assistants must be thanked for their efforts and enthusiasm.

Kurt Hunter-Mann

The second phase of excavation reinforced the findings of the first. Hopefully, the evidence that such an important, substantial building lies beneath the car park surface will result in a modification of the proposed development, so that St George's Chapel suffers no further depredation.

Thanks are due to York City Council, which funded the project and provided every assistance. Finally, the excavation assistants must be thanked for their efforts and enthusiasm.

Kurt Hunter-Mann