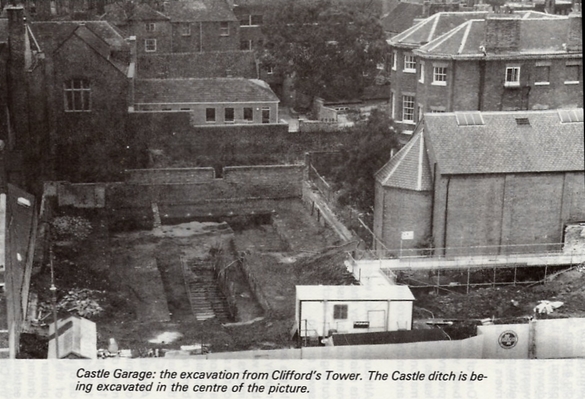

Castle Garage

All excavations have a way of producing the unexpected and nowhere has this been truer than at the site of the former Castle Garage in Tower Street. The excavation was planned with a view to examining the buildings of York's Franciscan Friary, for a reference in the Calendar Patent Rolls suggested that the Friary church was just inside a gateway to the Friary precinct opposite the church of St Mary Castlegate. It was thought, therefore, that the excavation would quickly bring us to the heart of the Friary and possibly reveal part of the church itself.

However, no Friary buildings have been uncovered and it is unlikely that the area was part of the original precinct, established in 1243: the ground here would have been too unstable for buildings as it was the site of a large ditch which must form part of York Castle defences. The Calendar Patent Rolls state that in 1268 a royal grant of a ditch was made to the Friars on the east side of their original site on condition that it was enclosed with an earthen bank. The ditch now being excavated is presumably the ditch referred to, and it was probably given to the Friars by King Henry III when it was no longer needed for the defence of the Castle.

In 1068 William the Conqueror founded two castles in York, one on each side of the Ouse, as part of his defence of the city against the local inhabitants and their Danish allies. Today the most prominent feature of the castle on the east side of the Ouse is the mound or 'motte' on which Cliffords Tower stands; it is also known that there was a bailey to the south east of the motte, the area of which can still be partly determined from the remains of its later medieval stone wall, and the castle was surrounded by a system of moats into which the River Foss was diverted. The exact nature of the defences to the north-west of the motte has never been fully understood, but it can now be suggested that there was a small defended area, perhaps a barbican rather than a bailey, between the ditch at the base of the motte and the ditch which has just been found.

Although for reasons of time, money and safety it will only be possible to dig a trench 3m wide through to the bottom of the ditch, it is already apparent that it is 24m wide, 5m deep, and that its sides slope fairly sharply down to a wide, flat bottom. The ditch runs roughly north-east - south-west though the site but it is not easy to say where it might run to - it may either curve round to meet the ditch around the motte or run directly to the rivers Foss and Ouse.

One of the most exciting aspects of the ditch is that the soil infilling it has been waterlogged since deposition. Organic material is therefore well preserved and large quantities of wood, leather, and plant material such as leaves, twigs and nuts have been recovered. This will provide much information on fhe life-style of two of the major institutions of the medieval city and on the micro-environment of the ditch at different stages of its infilling.

Although the ditch was probably kept well cleared out in the early years of its existence by the early 13th century it appears to have become a stagnant muddy area used for dumping rubbish. A smaller ditch or gully, found cutting into the ditch fill, ran down from the Castle and probably served as a sewer or drain.

In the later 13th century when the Friars acquired the site, the ditch was rapidly filled up with domestic rubbish and large quantities of pottery and bone were found in its upper layers. Some small drains and gullies were dug into its top and these presumably originated in Friary buildings to the west of the site. Perhaps the most significant event in the later medieval period is a major ground clearance which removed all the Roman and early medieval deposits. This was probably done to gather enough material to create the bank referred to in 1268. Unfortunately the excavations have yet to locate this bank but it may yet be possible to do so on the Tower Street frontage.

After the dissolution of the religious houses by Henry VIII in 1538, the area occupied by the Franciscan Friary was divided up into small properties, many of which survive today. According to maps of York made in the 17th and 19th centuries the site remained largely open ground until the late 19th century. When Castlegate House was built on Tower Street in the middle of the 18th century it had a formal garden with a sunken lawn in the area of the excavation and the many elongated pits containing rubble and plaster which were found on the site were probably dug then for lawn drainage. ln the later 19th and early 20th century other buildings were established on the Tower Street and Castlegate frontages and in the 1930s the Castle Garage was built over the filled-in sunken garden of Castlegate House.

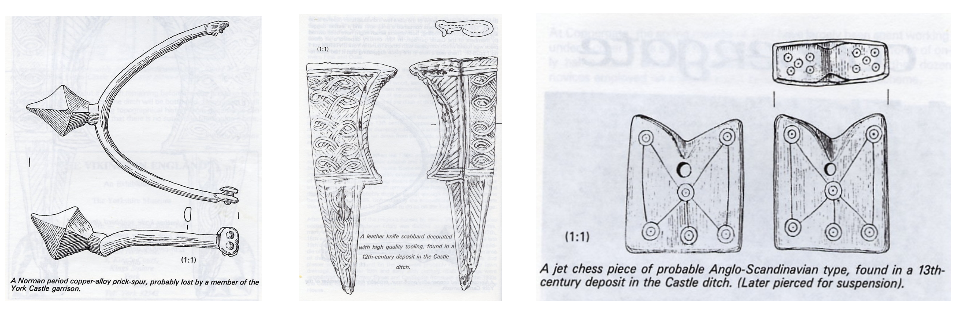

Before concluding this review of the site a few individual finds deserve to be noted. 12th century deposits contained a prick-spur and a leather dagger sheath with decorative tooling, both objects which might have been owned by members of the Castle garrison. In 13th century deposits a jet chess piece was found which compares with others found in York (INTERIM vol 1no 1 pp28-9). There was a hole in the piece suggesting that it had been reused as a pendant.

However, no Friary buildings have been uncovered and it is unlikely that the area was part of the original precinct, established in 1243: the ground here would have been too unstable for buildings as it was the site of a large ditch which must form part of York Castle defences. The Calendar Patent Rolls state that in 1268 a royal grant of a ditch was made to the Friars on the east side of their original site on condition that it was enclosed with an earthen bank. The ditch now being excavated is presumably the ditch referred to, and it was probably given to the Friars by King Henry III when it was no longer needed for the defence of the Castle.

In 1068 William the Conqueror founded two castles in York, one on each side of the Ouse, as part of his defence of the city against the local inhabitants and their Danish allies. Today the most prominent feature of the castle on the east side of the Ouse is the mound or 'motte' on which Cliffords Tower stands; it is also known that there was a bailey to the south east of the motte, the area of which can still be partly determined from the remains of its later medieval stone wall, and the castle was surrounded by a system of moats into which the River Foss was diverted. The exact nature of the defences to the north-west of the motte has never been fully understood, but it can now be suggested that there was a small defended area, perhaps a barbican rather than a bailey, between the ditch at the base of the motte and the ditch which has just been found.

Although for reasons of time, money and safety it will only be possible to dig a trench 3m wide through to the bottom of the ditch, it is already apparent that it is 24m wide, 5m deep, and that its sides slope fairly sharply down to a wide, flat bottom. The ditch runs roughly north-east - south-west though the site but it is not easy to say where it might run to - it may either curve round to meet the ditch around the motte or run directly to the rivers Foss and Ouse.

One of the most exciting aspects of the ditch is that the soil infilling it has been waterlogged since deposition. Organic material is therefore well preserved and large quantities of wood, leather, and plant material such as leaves, twigs and nuts have been recovered. This will provide much information on fhe life-style of two of the major institutions of the medieval city and on the micro-environment of the ditch at different stages of its infilling.

Although the ditch was probably kept well cleared out in the early years of its existence by the early 13th century it appears to have become a stagnant muddy area used for dumping rubbish. A smaller ditch or gully, found cutting into the ditch fill, ran down from the Castle and probably served as a sewer or drain.

In the later 13th century when the Friars acquired the site, the ditch was rapidly filled up with domestic rubbish and large quantities of pottery and bone were found in its upper layers. Some small drains and gullies were dug into its top and these presumably originated in Friary buildings to the west of the site. Perhaps the most significant event in the later medieval period is a major ground clearance which removed all the Roman and early medieval deposits. This was probably done to gather enough material to create the bank referred to in 1268. Unfortunately the excavations have yet to locate this bank but it may yet be possible to do so on the Tower Street frontage.

After the dissolution of the religious houses by Henry VIII in 1538, the area occupied by the Franciscan Friary was divided up into small properties, many of which survive today. According to maps of York made in the 17th and 19th centuries the site remained largely open ground until the late 19th century. When Castlegate House was built on Tower Street in the middle of the 18th century it had a formal garden with a sunken lawn in the area of the excavation and the many elongated pits containing rubble and plaster which were found on the site were probably dug then for lawn drainage. ln the later 19th and early 20th century other buildings were established on the Tower Street and Castlegate frontages and in the 1930s the Castle Garage was built over the filled-in sunken garden of Castlegate House.

Before concluding this review of the site a few individual finds deserve to be noted. 12th century deposits contained a prick-spur and a leather dagger sheath with decorative tooling, both objects which might have been owned by members of the Castle garrison. In 13th century deposits a jet chess piece was found which compares with others found in York (INTERIM vol 1no 1 pp28-9). There was a hole in the piece suggesting that it had been reused as a pendant.

At present there is about a month remaining before the site is due to finish but by then it is expected that the ditch will be bottomed. Once again it will have been shown that inferring topographical history from documents can be dangerously deceptive and that there is no substitute for digging a hole.

Patrick Ottaway.

Patrick Ottaway.