For Anglo-Saxonists with any streak of the romantic in them, the most pleasing find of the Trust's summer excavations must be the small cross found in the Cattle Market site, which is certainly a relic of Anglian York. It is gratifying enough to tearn of any finds at all being made outside the predictable area of the Minster for this hitherto archaeologically elusive period. But the discovery of this cross and related materials not only labels the Cattle Market region as a likely Anglian suburb of early date; it also offers a date within a momentous period of York’s church history.

The location of the cross was in the top of a well long since disused into which a wattle and daub wail had slipped. Domestic refuse containing vegetable matter and bones (but no pottery) had been thrown into the depression and among this lay the cross and two Anglo-Saxon coins.

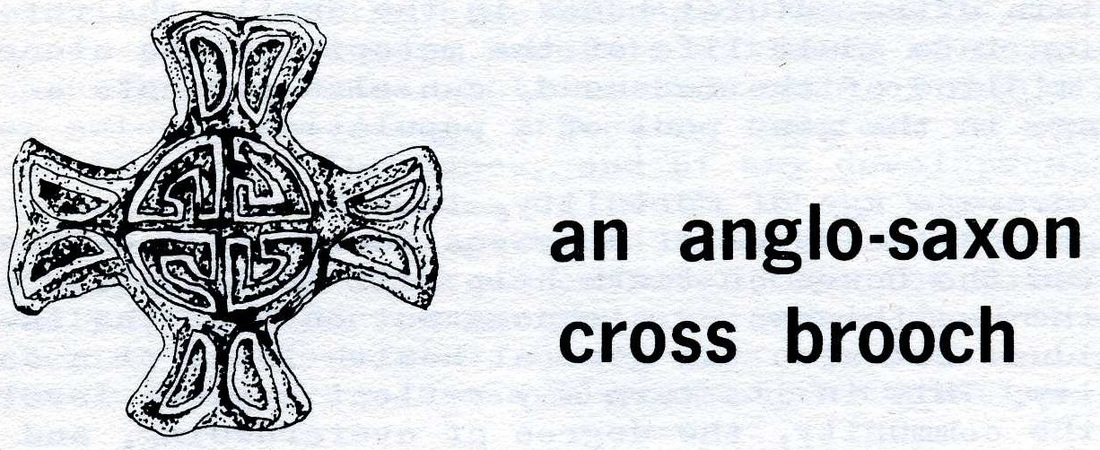

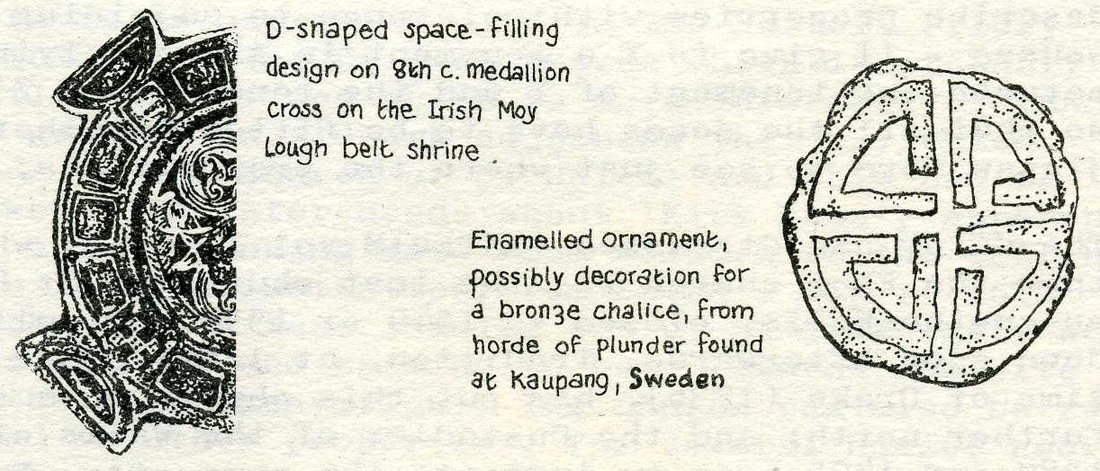

The cross is of the Celtic type - closely paralleled in its shape among Irish and Manx stone crosses and decoration in Irish manuscripts or manuscripts showing strong Irish influence (see, for example, the two illustrations). The arms are equal in length and around their intersection is developed a circular decorative area which intrudes into the angles between the arms. It is about 32mm square and cast in bronze about 2mm thick. A slightly irregular edge has been turned back and beaten roughly down forming an uneven rim on the backside - which is completely undecorated and obviously not intended to be seen. On the back are two lugs standing about 7mm high, 5mm wide and 1mm thick, each pierced with a round hole. These lugs are placed in such a way that the holes are not face to face so that a straight pin could be pushed through. Instead they lay in such a way that two separate pins or s staple-shaped fastener would be required. It is possible that the cross was sewn on to something - a hat or a robe. But the length of the lugs might suggest that it was intended to be fastened through a rigid material of substantial thickness: it might for example be a decorative detail from some object of wood or metal, rather than a personal brooch.

The decoration on the face of the cross is skillfully enough done by a cloisonné technique used by the Celts but highly characteristic of Anglo-Saxon workmanship. Within raised ‘walls’ of metal a symmetrical pattern is made of ‘cells’. Though on this cross these cells are now empty, it might be assumed, by the example of amply surviving instances of this technique, that they were originally filled with gems - for example garnet - or coloured enamel. Traces of a yellow substance like yellow enamel used in Anglo-Saxon ornament do in fact show in some of the cells, though these may prove to be natural chemical discolourings. The workmanship is not of the very highest order. Apart from the rough finish given to the back, there is a lack of perfect symmetry in the arms of the cross which do not match exactly in size. A small hole right through the bottom of one cell has a slight rim on the backside and a curve which suggests it was made by a clumsily tapped engraving tool.

The ends of the arms are not square, but bifurcated. The shape thus created is ideal for decoration with the interlace pattern so common in Celtic and Anglo-Saxon art. But instead a very simple design has been chosen consisting of two crescent moon shaped cells back to back and filling the space between the centre medallion and the end of the arms. The centre piece itself is also simply though attractively designed. The single motif is repeated in each of the quadrants into which the circle is divided, thus forming a swastika-cross. The whole decoration is plain and sober, compared with the exuberance that can be expressed with interlace pattern, in Irish stone crosses of this period, or (nearer home) in the cross-patterns in the base of the Ormside Bowl (Yorkshire Museum).

The coins associated with the cross confirm the date which its form and decoration most strongly suggest: the 8th century. Both coins are of silver mixed with bronze bearing on the reverse side the figure of a fantastic animal and on the obverse the name of king Eadberht of Northumbria.

The location of the cross was in the top of a well long since disused into which a wattle and daub wail had slipped. Domestic refuse containing vegetable matter and bones (but no pottery) had been thrown into the depression and among this lay the cross and two Anglo-Saxon coins.

The cross is of the Celtic type - closely paralleled in its shape among Irish and Manx stone crosses and decoration in Irish manuscripts or manuscripts showing strong Irish influence (see, for example, the two illustrations). The arms are equal in length and around their intersection is developed a circular decorative area which intrudes into the angles between the arms. It is about 32mm square and cast in bronze about 2mm thick. A slightly irregular edge has been turned back and beaten roughly down forming an uneven rim on the backside - which is completely undecorated and obviously not intended to be seen. On the back are two lugs standing about 7mm high, 5mm wide and 1mm thick, each pierced with a round hole. These lugs are placed in such a way that the holes are not face to face so that a straight pin could be pushed through. Instead they lay in such a way that two separate pins or s staple-shaped fastener would be required. It is possible that the cross was sewn on to something - a hat or a robe. But the length of the lugs might suggest that it was intended to be fastened through a rigid material of substantial thickness: it might for example be a decorative detail from some object of wood or metal, rather than a personal brooch.

The decoration on the face of the cross is skillfully enough done by a cloisonné technique used by the Celts but highly characteristic of Anglo-Saxon workmanship. Within raised ‘walls’ of metal a symmetrical pattern is made of ‘cells’. Though on this cross these cells are now empty, it might be assumed, by the example of amply surviving instances of this technique, that they were originally filled with gems - for example garnet - or coloured enamel. Traces of a yellow substance like yellow enamel used in Anglo-Saxon ornament do in fact show in some of the cells, though these may prove to be natural chemical discolourings. The workmanship is not of the very highest order. Apart from the rough finish given to the back, there is a lack of perfect symmetry in the arms of the cross which do not match exactly in size. A small hole right through the bottom of one cell has a slight rim on the backside and a curve which suggests it was made by a clumsily tapped engraving tool.

The ends of the arms are not square, but bifurcated. The shape thus created is ideal for decoration with the interlace pattern so common in Celtic and Anglo-Saxon art. But instead a very simple design has been chosen consisting of two crescent moon shaped cells back to back and filling the space between the centre medallion and the end of the arms. The centre piece itself is also simply though attractively designed. The single motif is repeated in each of the quadrants into which the circle is divided, thus forming a swastika-cross. The whole decoration is plain and sober, compared with the exuberance that can be expressed with interlace pattern, in Irish stone crosses of this period, or (nearer home) in the cross-patterns in the base of the Ormside Bowl (Yorkshire Museum).

The coins associated with the cross confirm the date which its form and decoration most strongly suggest: the 8th century. Both coins are of silver mixed with bronze bearing on the reverse side the figure of a fantastic animal and on the obverse the name of king Eadberht of Northumbria.

Eadberht peacefully succeeded his cousin Ceolwulf (who abdicated to become a monk) in 737. Of his reign little is recorded, though he may be the Northumbrian king who gained great victories against the Strathclyde Britons (Welsh) and captured their royal city of Dumbarton just after the mid-8th century. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle mentions that Æthelbald of Mercia harried Northumbira in the very year of Eadberht's succession, and that York was burnt down in 741, but otherwise Northumbrian affairs for this period barely feature there. Eadberht rules until 758 and then, like his cousin, entered a monastery, passing on the crown to his son Oswulf who, however, was murdered a year later by one of his own household. When Eadberht died in 768 he was, the Chronicle says, buried in York in the same chapel as his brother, Archbishop Egbert, who had died two years previously.

Egbert has a much more definite and distinguished place in English history than his brother, for he it was who, with the powerful support of the Venerable Bede, persuaded the Pope to send once more the archbishop’s pallium which had been intended for Paulinus a century earlier, but which Edwin’s death in war and the flight of Paulinus forestalled. The text of the letter still survives which Bede wrote to Egbert at York on 5 November 734, advising him that if only Egbert would make certain reforms in his bishopric it was most likely that York would at last be raised to metropolitan status as had been expressed purpose of Pope Gregory when he sent Augustine to convert the English. And so it was, in the year of Bede's death, 735 Egbert became the first archbishop of York, and the Roman hierarchy of the church in Northumbria was now complete, as it had been long since in the South. Yet the Celtic church, which had played such a fundamental part in the Christianisation of the North, but had been in retreat since its defeat at the Synod of Whitby in 664, left its legacy in Northumbria - not in the form of church organisation and practice but in that sense of the beauty of holiness so pronounced in Northumbrian religious art, as in the great stone crosses and the illuminated gospel books.

The small cross from the Cattle Market site is a memento of the York which Bede knew and visited where Celtic met Roman under the patronage of Anglo-Saxon kings.

S.A.J. Bradley